Street View as a game engine: Localised sounds

This is the first post in a “Making of” series for my new web-based game, Finding Gustavo. In this series, I talk about the various techiques I used to turn Google Street View into a (sort of) game engine. While reading the post, it helps to be somewhat familiar with programming, ideally in JavaScript.

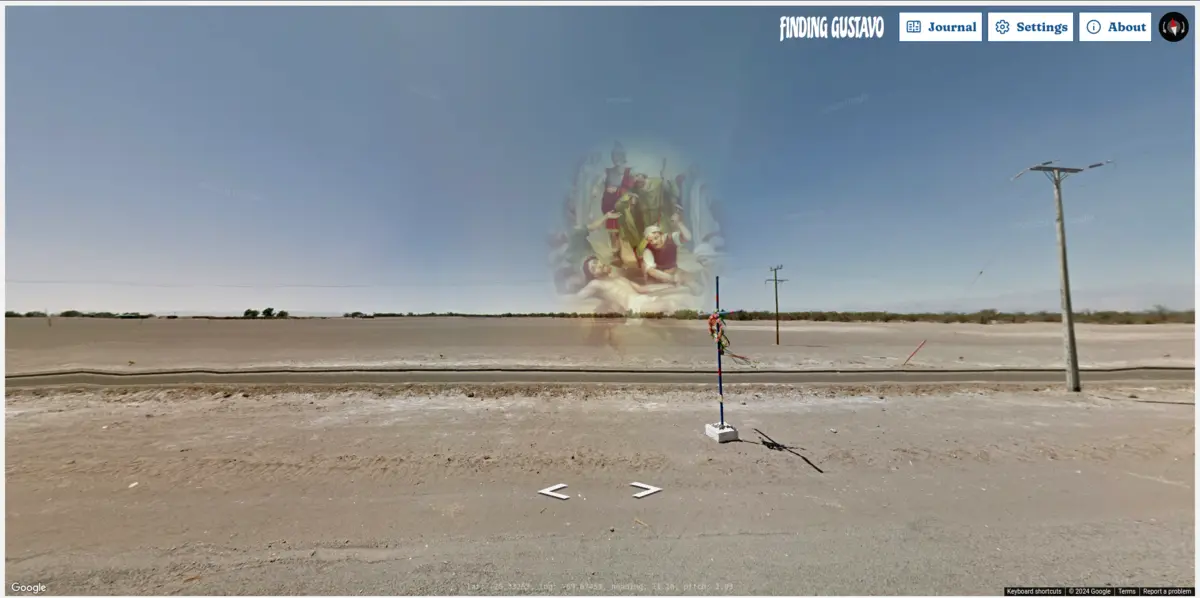

As I’m writing this, Google Street View has been around for almost two decades. Not only is it very useful and an incredible feat of engineering, it’s also found its use as a creative tool. People have made music videos and audio tours with it, and perhaps most famously, a game called GeoGuessr became a world sensation during the pandemic, dropping players onto random spots on the planet and letting them guess their location based on what they see. My goal with this project was to find out just how close to a proper game engine Street View could get. Since the visuals and navigation have already been implemented by Google, the next logical step was to add sound. My implementation is largely based on the Sharawadji project developed with Tim Cowlishaw in 2019.

In film theory, sounds can be classified into two groups: the so-called diegetic sounds originate within the world itself - e.g. footsteps, speech, birdsong in the background. Non-diegetic sounds are still part of the story, but are understood to exist outside of the world - these include the (often musical) sound-track and some additional sound effects that augment the viewing experience. In computer games, this distinction exists, too, but diegetic sound becomes a lot more complex, because the listener’s position and orientation changes interactively. That is, we do not have control over when and where the player will hear any given diegetic sound.

In this post, I’ll assume you are able to embed a Street View “panorama” using the Google Maps API. To implement diegetic (or in this context, “localised”) sounds, every time the player moves in-game we’ll need to answer the following questions:

- Where are the player and the sound right now?

- What is the sound’s orientation and volume in relation to the player?

- When do we load, start and stop playing the sound?

Reacting to the Player’s position

A peculiar thing about building a game with Street View is that we have little control over what exactly happens in Street View itself. The Google Maps API provides a lot of useful methods for controlling the experience programmatically, but at the end of the day, it’s a dynamically loaded piece of software we do not control. That’s why the “game engine” we’re building has to use Street View as its source of truth. In a sense, everything that happens in the game is a function of the Player’s position and orientation within Street View. This is also reflected on by the narrator in the first moments of Finding Gustavo:

What is a world, if not a series of multisensory images, presented to us as a function of latitude, longitude, heading and pitch?

To react to the Player’s position, we can listen to the position_changed event on the StreetViewPanorama object. Every time the event fires, we’ll get the current position and update our sound mix (more on that later). The position is 2-dimensional and corresponds to the world coordinates of the player - their latitude and longitude.

const panorama = new StreetViewPanorama(document.getElementById('panorama'));

const updateMix = () => {

// to be implemented

};

panorama.addListener('position_changed', () => {

console.log(panorama.getPosition()); // returns a `LatLng` object with `lat()` and `lng()` methods

updateMix();

});

We can do the same for the Player’s orientation, i.e. which direction they’re looking. In Street View, this is a three-dimensional number consisting of heading (horizontal orientation), pitch (vertical orientation) and zoom (controlled by scrolling or pinching on touch screens). For our purposes, zoom does not affect the sound mix - we assume the player is standing still while zooming, so the spatial relationship to our diegetic sound doesn’t change. Our eyes have no zoom functionality, after all.

panorama.addListener('pov_changed', () => {

console.log(panorama.getPov()); // returns a plain, serialisable object with `{ heading, pitch, zoom }`

updateMix();

});

The position and orientation of our Player/listener can now be compared with the position of our sound. Many sound sources in the real world (e.g. a human voice) project sound in a specific direction, but for simplicity, we can assume the sound emanates from the source in all directions equally (this is a good model for complex sounds such as the rustling of a forest, or the hum of highway traffic). This means our sound can simply be described in terms of its latitude and longitude (and of course, the audio samples required to play it).

const localisedSound = {

name: "dogs-barking",

lat: -20.435150980335941,

lng: -69.545929008780504,

src: "/assets/audio/dogs-barking.mp3",

};

Mixing the localised sound in 3D

Now that we have the required information about the Player and the localised sound, we can set up a Web Audio graph to play and mix our sound. We start by creating an AudioContext and creating a few necessary nodes.

const context = new AudioContext();

// Create our source node and make it loop forever

const source = new AudioBufferSourceNode(context, { loop: true });

// The PannerNode allows us to position the sound in 3D (best heard when using headphones)

// The HRTF panning model gives the best possible results, though it's more computationally intensive.

const panner = new PannerNode(context, { panningModel: 'HRTF', distanceModel: 'linear' });

// The PannerNode does reduce the volume as the listener moves away,

// but we want the sound to completely fade out at some point, so we need our own volume control.

const volume = new GainNode(context, { gain: 0 });

// Connect nodes and plug them into our destination (normally, this is the computer's default audio output device)

// We don't connect the `source` yet.

panner

.connect(volume)

.connect(context.destination);

Having set up our graph, our updateMix function can modify it in response to the player’s position changing. First, we position the AudioContext.listener (which represents the player).

const position = panorama.getPosition();

// setting `.value` is a quick way to instantly update the `positionX` parameter. It can also be updated gradually using other Web Audio API methods.

context.listener.positionX.value = position.lat();

context.listener.positionY.value = position.lng();

Then we must set the listener’s orientation to match the heading and pitch in Street View. The AudioListener orientation is expressed as two three-dimensional vectors - forward and up.

You can think of them as two arrows pointing somewhere in 3D space. To calculate the forward and up vector values, we need to convert our existing heading and pitch values (which come in degrees) to normalised vector values. I’ve included a function that calculates the vectors below:

Show full code for calculateListenerOrientation

// this function converts rotation angles to forward and up vectors

// we use the aircraft terms – HEADING (a.k.a Yaw) and PITCH – to denote axes of rotation

// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aircraft_principal_axes

// We omit ROLL because in our use case, there is no way to tilt around the Z axis.

// We use trigonometric functions to establish relationships between the vectors

// and ensure they each circumscribe a sphere as they rotate.

const calculateListenerOrientation = (heading = 0, pitch = 0) => {

// vector determining which way the listener is facing

const forward = {};

// vector determining the rotation of the listener's head

// where no rotation means the head is pointing up

const up = {};

// Heading is the rotation around the Y axis

// convert to radians first

const headingRad = heading * (Math.PI / 180);

// at 0 degrees, the X component should be 0

//so we calculate it using sin(), which starts at 0

forward.x = Math.sin(headingRad);

// at 0 degrees, the Z component should be -1,

// because the negative Z axis points *away from* the listener

// so we calculate it using cos(), which starts at 1

// with a phase shift of 90 degrees (or PI radians)

forward.z = Math.cos(headingRad + Math.PI);

// Pitch is the rotation around the X axis

// we can use it to calculate both vectors' Y components

const pitchRad = pitch * (Math.PI / 180);

// Forward Y component should start at 0

forward.y = Math.sin(pitchRad);

// Up Y component should start at 1 (top of the head pointing up)

up.y = Math.cos(pitchRad);

// Roll is the rotation around the Z axis.

// Because we ignore it in this case, both X and Y components are set to 0

// (top of the head pointing directly upwards).

up.x = 0;

up.z = 0;

return { forward, up };

};

Now we can apply our vectors to the listener:

const { heading, pitch } = panorama.getPov();

const { forward, up } = calculateListenerOrientation(heading, pitch);

context.listener.forwardX.value = forward.x;

context.listener.forwardY.value = forward.y;

context.listener.forwardZ.value = forward.z;

context.listener.upX.value = up.x;

context.listener.upY.value = up.y;

context.listener.upZ.value = up.z;

All that remains now is to position our localised sound, i.e. the panner itself. Since the listener’s position is expressed using latitude/longitude,

we can do the same for the sound.

panner.positionX.value = localisedSound.lat;

panner.positionY.value = localisedSound.lng;

Adjusting the localised sound’s volume

As mentioned above, the PannerNode automatically adjusts the sound’s volume as the listener moves closer or further away. However, in our scenario,

we want the sound to disappear altogether at some point. To do this, we adjust the volume ourselves. We calculate the distance between the listener and the sound

using a latLngDist function, then use the Inverse Square Law to derive the gain value from the distance. To avoid the volume jumping abruptly, we

schedule a gradual “ramp” to the target value over 2 seconds.

// Calculate the distance between listener and sound.

// Use plain objects (`{ lat, lng }`) for positions when passed to `latLngDist`.

const distance = latLngDist({ lat: position.lat(), lng: position.lng() }, localisedSound);

// Calculate target gain using the Inverse Square Law, limiting it to 1 or less.

const targetGain = Math.min(1 / distance ** 2, 1);

// Gradually change the `gain` value so it reaches `targetGain` 2 seconds from now.

volume.gain.linearRampToValueAtTime(targetGain, context.currentTime + 2);

Show full code for latLngDist

const EARTH_RADIUS = 6378137;

// converts degrees to radians

const rad = x => x * Math.PI / 180;

const latLngDist = (p1, p2) => {

const dLat = rad(p2.lat - p1.lat);

const dLong = rad(p2.lng - p1.lng);

const a =

Math.sin(dLat / 2) ** 2 +

Math.cos(rad(p1.lat)) *

Math.cos(rad(p2.lat)) *

Math.sin(dLong / 2) ** 2;

return EARTH_RADIUS * 2 * Math.atan2(Math.sqrt(a), Math.sqrt(1 - a));

};

Loading, starting and stopping playback

In a game, there could be dozens, or even hundreds of diegetic localised sounds. A web-based game like Finding Gustavo is

served over the network and could be played on all kinds of slow connections. That’s why it’s important we only ever load and play the sounds necessary at any given point.

Once the sound becomes audible, it already needs to be playing, so we want to call the start() method on the source before that happens.

Similarly, before the sound file is played, it must already be loaded and decoded, so we want to send the HTTP request and decode the file some time before start() is called.

We can say the sound can be in 4 different states - let’s make a constant for each of them:

const IDLE = 0; // player hasn't come near this sound yet

const LOADING = 1; // or decoding

const SUSPENDED = 3; // sound has been loaded and decoded, but the player is too far to hear it

const PLAYING = 4; // sound has been loaded and decoded and is near enough to play

localisedSound.state = IDLE;

Every time the player’s position changes, we can use the distance from our sound to determine which state it should be in. But first, let’s define a function to load and decode our sound:

const load = async (localisedSound) => {

localisedSound.state = LOADING;

const response = await fetch(localisedSound.src);

// this will work everywhere except Safari, where `decodeAudioData` doesn't return a Promise

source.buffer = await context.decodeAudioData(await response.arrayBuffer());

localisedSound.state = SUSPENDED;

};

In our updateMix function, we can now update the sound’s state. Since Web Audio source nodes can only be played once,

once start() has been called, we only disconnect and connect the node as needed, never stopping the playback.

// thresholds can be tweaked, these were determined by trial-and-error for Finding Gustavo

const PLAY_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD = 300;

const LOAD_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD = PLAY_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD + 20;

// const updateMix = () => {

// ...

switch(localisedSound.state) {

case LOADING:

return;

case PLAYING:

if (distance >= PLAY_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD) {

console.info('suspending', localisedSound.name);

source.disconnect();

localisedSound.state = SUSPENDED;

return;

}

break;

case SUSPENDED:

if (distance < PLAY_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD) {

console.info('starting', localisedSound.name);

source.connect(processingChainStart);

source.start(); // on repeated calls, this will fail silently

state = Sound.state.PLAYING;

} else {

return;

}

break;

case IDLE:

default:

if (distance < LOAD_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD) {

try {

load(localisedSound);

} catch(e) {

console.warn(`Couldn't load ${localisedSound.src}`);

}

return;

} else {

return;

}

break;

}

// ...

// }

Conclusion

And that’s it! Our sound is now efficiently loaded only when needed, and once played back, it can be heard coming from the location we placed it in the world of Street View. We can extend this technique in a number of ways, e.g. by limiting the number of sounds that can play simultaneously (or attenuating them accordingly) to avoid distortion when too many sounds are crammed through the speakers.

Here's all the code from this post put together (though you might want to structure it differently for your application)

// thresholds can be tweaked, these were determined by trial-and-error for Finding Gustavo

const PLAY_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD = 300;

const LOAD_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD = PLAY_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD + 20;

const EARTH_RADIUS = 6378137;

const IDLE = 0; // player hasn't come near this sound yet

const LOADING = 1; // or decoding

const SUSPENDED = 3; // sound has been loaded and decoded, but the player is too far to hear it

const PLAYING = 4; // sound has been loaded and decoded and is near enough to play

// converts degrees to radians

const rad = x => x * Math.PI / 180;

const latLngDist = (p1, p2) => {

const dLat = rad(p2.lat - p1.lat);

const dLong = rad(p2.lng - p1.lng);

const a =

Math.sin(dLat / 2) ** 2 +

Math.cos(rad(p1.lat)) *

Math.cos(rad(p2.lat)) *

Math.sin(dLong / 2) ** 2;

return EARTH_RADIUS * 2 * Math.atan2(Math.sqrt(a), Math.sqrt(1 - a));

};

// this function converts rotation angles to forward and up vectors

// we use the aircraft terms – HEADING (a.k.a Yaw) and PITCH – to denote axes of rotation

// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aircraft_principal_axes

// We omit ROLL because in our use case, there is no way to tilt around the Z axis.

// We use trigonometric functions to establish relationships between the vectors

// and ensure they each circumscribe a sphere as they rotate.

const calculateListenerOrientation = (heading = 0, pitch = 0) => {

// vector determining which way the listener is facing

const forward = {};

// vector determining the rotation of the listener's head

// where no rotation means the head is pointing up

const up = {};

// Heading is the rotation around the Y axis

// convert to radians first

const headingRad = heading * (Math.PI / 180);

// at 0 degrees, the X component should be 0

//so we calculate it using sin(), which starts at 0

forward.x = Math.sin(headingRad);

// at 0 degrees, the Z component should be -1,

// because the negative Z axis points *away from* the listener

// so we calculate it using cos(), which starts at 1

// with a phase shift of 90 degrees (or PI radians)

forward.z = Math.cos(headingRad + Math.PI);

// Pitch is the rotation around the X axis

// we can use it to calculate both vectors' Y components

const pitchRad = pitch * (Math.PI / 180);

// Forward Y component should start at 0

forward.y = Math.sin(pitchRad);

// Up Y component should start at 1 (top of the head pointing up)

up.y = Math.cos(pitchRad);

// Roll is the rotation around the Z axis.

// Because we ignore it in this case, both X and Y components are set to 0

// (top of the head pointing directly upwards).

up.x = 0;

up.z = 0;

return { forward, up };

};

const load = async (localisedSound) => {

localisedSound.state = LOADING;

const response = await fetch(localisedSound.src);

// this will work everywhere except Safari, where `decodeAudioData` doesn't return a Promise

source.buffer = await context.decodeAudioData(await response.arrayBuffer());

localisedSound.state = SUSPENDED;

};

const updateMix = (panorama, localisedSound) => {

switch(localisedSound.state) {

case LOADING:

return;

case PLAYING:

if (distance >= PLAY_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD) {

console.info('suspending', localisedSound.name);

source.disconnect();

localisedSound.state = SUSPENDED;

return;

}

break;

case SUSPENDED:

if (distance < PLAY_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD) {

console.info('starting', localisedSound.name);

source.connect(processingChainStart);

source.start(); // on repeated calls, this will fail silently

state = Sound.state.PLAYING;

} else {

return;

}

break;

case IDLE:

default:

if (distance < LOAD_DISTANCE_THRESHOLD) {

try {

load(localisedSound);

} catch(e) {

console.warn(`Couldn't load ${localisedSound.src}`);

}

return;

} else {

return;

}

break;

}

const position = panorama.getPosition();

// setting `.value` is a quick way to instantly update the `positionX` parameter. It can also be updated gradually using other Web Audio API methods.

context.listener.positionX.value = position.lat();

context.listener.positionY.value = position.lng();

const { heading, pitch } = panorama.getPov();

const { forward, up } = calculateListenerOrientation(heading, pitch);

context.listener.forwardX.value = forward.x;

context.listener.forwardY.value = forward.y;

context.listener.forwardZ.value = forward.z;

context.listener.upX.value = up.x;

context.listener.upY.value = up.y;

context.listener.upZ.value = up.z;

panner.positionX.value = localisedSound.lat;

panner.positionY.value = localisedSound.lng;

// Calculate the distance between listener and sound.

// Use plain objects (`{ lat, lng }`) for positions when passed to `latLngDist`.

const distance = latLngDist({ lat: position.lat(), lng: position.lng() }, localisedSound);

// Calculate target gain using the Inverse Square Law, limiting it to 1 or less.

const targetGain = Math.min(1 / distance ** 2, 1);

// Gradually change the `gain` value so it reaches `targetGain` 2 seconds from now.

volume.gain.linearRampToValueAtTime(targetGain, context.currentTime + 2);

};

const context = new AudioContext();

// Create our source node and make it loop forever

const source = new AudioBufferSourceNode(context, { loop: true });

// The PannerNode allows us to position the sound in 3D (best heard when using headphones)

// The HRTF panning model gives the best possible results, though it's more computationally intensive.

const panner = new PannerNode(context, { panningModel: 'HRTF', distanceModel: 'linear' });

// The PannerNode does reduce the volume as the listener moves away,

// but we want the sound to completely fade out at some point, so we need our own volume control.

const volume = new GainNode(context, { gain: 0 });

// Connect nodes and plug them into our destination (normally, this is the computer's default audio output device)

// We don't connect the `source` yet.

panner

.connect(volume)

.connect(context.destination);

const localisedSound = {

name: "dogs-barking",

lat: -20.435150980335941,

lng: -69.545929008780504,

src: "/assets/audio/dogs-barking.mp3",

};

const panorama = new StreetViewPanorama(document.getElementById('panorama'));

panorama.addListener('position_changed', () => updateMix(panorama, localisedSound));

panorama.addListener('pov_changed', () => updateMix(panorama, localisedSound));

To see the localised sounds technique in action, try out Finding Gustavo at

https://finding-gustavo.quest. In the next post, I will show

how I’ve embedded interactive 3D objects into the Street View world using Three.js and some funky hacks. Until next time!